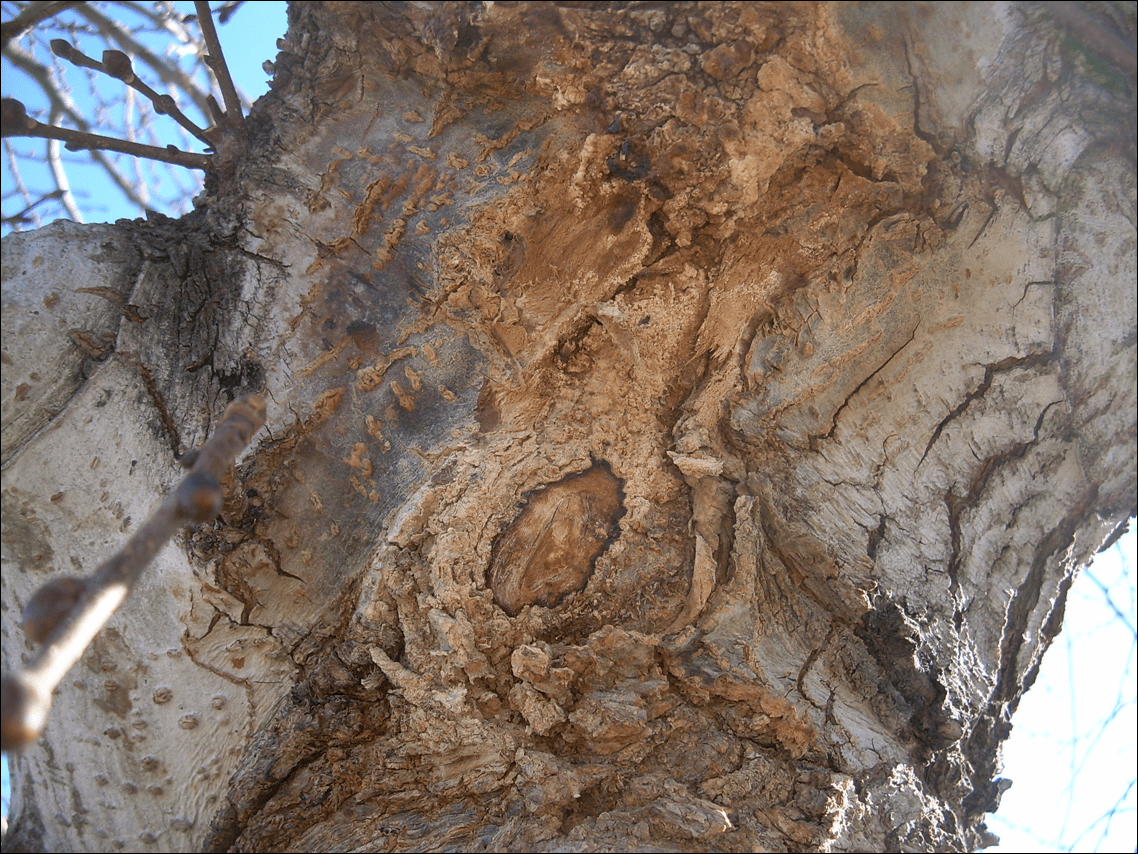

Stained bark from wetwood fluids is commonly observed on mature elms in the landscape. Wetwood slime stains the bark and when dry it appears gray, pale brown to yellow in color. This is how the term “slime flux” became popularized, especially when the fluid was forcibly sprayed out of pruning cuts. This thick, slime-like fluid is often dark in color as it streams down branches or the main trunk. Free-living bacteria, yeasts and filamentous fungi on the surface of the bark are stimulated and grow within the fluid as well. The fluid is a mixture of bacterial and yeast cells and water. When this pressure is released, through a branch crotch, seam or pruning cut, large volumes of fluid can be released. Their metabolic actions lead to increases in gas pressure, primarily from methane. Within colonized heartwood tissues, wetwood bacteria help to infuse water into the wood, thriving in the anaerobic environment.

In elms, the symptoms may resemble Dutch elm disease, complete with vascular staining. These symptoms would manifest as leaf scorch, wilt and a general canopy dieback. At times, it has been shown that wetwood fluids under pressure expand radially into functional sapwood tissues, clogging xylem vessels and inducing water starvation. But, they lack the ability to cause decay that would result in reductions in wood density.

Wetwood bacteria do produce enzymes that can degrade primary cell walls and other intercellular material, causing some weakening of the wood. However, once established, wetwood bacteria colonize the heartwood tissues where they may persist for decades without ever causing any harm to the tree. Wetwood often develops in the roots or in the lower trunk of the tree, but over time it may be present high in the trunk or in major canopy branches. Wounds are the most common source of entry for wetwood bacteria. They must invade trees to establish but there is no evidence that this process causes necrosis to any live tissues in the roots, main trunk or branches.

#TREE SLIME FLUX FREE#

Several studies, using conifers and hardwoods, have shown that wood tissues colonized by wetwood bacteria exhibit higher decay resistance compared to uncolonized wood. Wetwood bacteria are both free living and common in soil and water. The lack of available oxygen in the saturated wood may prevent wood-rotting pathogens, like Armillaria for example, from establishing in the heartwood. There is also evidence that wetwood bacteria may provide some level of protection against wood-rotting fungi. Yet, for the majority of affected trees the presence of wetwood is inconsequential to their overall health. There are, however, cases where wetwood-induced bacterial growth appears to harm trees. In addition, fir ( Abies), hemlock ( Tsuga), sycamore ( Platanus), maple ( Acer), mulberry ( Morus), willow ( Salix) and oak ( Quercus) frequently harbor wetwood. Wetwood occurs in nearly all elm ( Ulmus) and poplar ( Populus) species.

Wood harboring these bacteria has a strong, pungent odor and can range in color from pinkish, yellow, olive-green, to dark brown. Wetwood often supports large populations of anaerobic bacteria from multiple genera, none of which are known to possess any host specificity. Wetwood is a condition in which the heartwood becomes water-soaked due to bacterial colonization.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)